MEET TODAY’S GUEST

Ellen Reynolds, Lavender Grower, Butterfly Steward, Mentor, and Community Builder

Ellen Reynolds turned a retirement plot into Beagle Ridge Farm–Lavender and Herbs—a remote destination that grew from quiet gardens into an artisan apothecary and a 32-species butterfly program. Today she mentors new growers through The Lavender Academy, supplies plants and products to farms from Missouri to New Hampshire, and is building the Lavender Association of America to connect and strengthen small lavender farms.

At the end of a gravel road in a valley between two mountains, a retirement daydream grew into a working model for rural resilience. Beagle Ridge is part destination, part small-batch factory, part classroom—and a vivid argument that collaboration, not competition, can anchor a local economy.

Hey there!

You’re reading the Argentabraid Journal — a homegrown journal for those reimagining work and life at the roots. Each issue shares stories from artisans, growers, and quiet builders shaping a parallel economy - where meaning matters more than metrics, and freedom is found in shared knowledge, mutual support, and creative sovereignty.

This is the thread between us.

— The Argentabraid Team

THE RIDGE STORY

Three and a Half Miles in, the Valley Shifts: People Visit, Learn, and Carry a Piece of the Ridge Home

The road in tells you almost everything you need to know about Beagle Ridge. It doesn’t invite the casual stop; it requires intention. Three and a half miles off the main road, the ridge opens into a sheltered bowl of hills where wind runs softer and time slows to the pace of plants. Visitors arrive here on purpose, not by accident—and they have, from forty-three countries and every U.S. state, often planning their East Coast drives to include a ritual stop, sometimes twice a year.

Ellen Reynolds laughs when she describes the origin story, crediting her husband’s shorthand: “Ellen started gardening and it got out of hand.” Twenty-four years ago, the couple bought land two hours from home to build a retirement house. Then the neighboring forty acres came up for sale—a former hunt club crowned by a colossal mid-century building that once raised roughly thirty thousand Chukar partridge and quail. Notables hunted there in its heyday; the lore lingers like the scent of crushed lavender. The Reynoldses purchased the property to steward its future. With a building, a valley, and a curious stream of visitors, the herb garden refused to stay small.

What emerged is Beagle Ridge Herb Farm and Environmental Educational Center—now on the cusp of its twenty-fifth anniversary and rebranding to Beagle Ridge Farm–Lavender and Herbs to reflect where the work naturally led. The name change isn’t cosmetic. It’s a practical truth about time and attention: environmental programming continues, but the core now is lavender and herbs—grown, distilled, formulated, taught, and shipped daily from a ridge that people first find on a map and then, unexpectedly, in their annual rituals.

The Work Behind the Welcome

From May through October, Beagle Ridge opens to the public Thursday through Sunday at 10 a.m. If the lanes are quiet at opening, the team moves product through small-batch runs, trims and mends two acres of formal gardens, and feeds butterflies. Classes run on and off year-round, both on-site and in town, so even when gates are closed the ridge hums with learning. Monday through Wednesday, the farm becomes a venue for groups—tour buses, garden clubs, and specialized programs that turn the valley into a classroom. About seventy-five percent of visitors are tourists, which tracks with the region’s role as a crossroads. The farm isn’t a place you stumble upon; it’s a place you seek out.

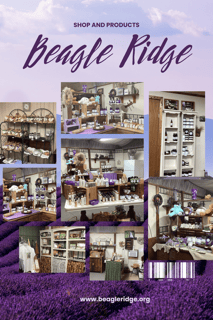

The welcome is warm, but the engine is manufacturing. Beagle Ridge produces 105 distinct items—soaps and lotions, shower gels and sachets, eye pillows, room sprays, and a growing line of face products. They’re made fresh weekly and shipped daily. Wholesale is the bread-and-butter, with Beagle Ridge manufacturing for twenty-six other farms and stores nationwide; the retail website supports rather than anchors revenue. Walk the building and you feel the cadence: measured, consistent, intimate. It’s craft scaled just enough to be sustainable.

Parallel to the apothecary work is a plant operation that is large by feel, not by fanfare: approximately 25,000 plants will be grown this coming year—an intentional reduction to match strategy and capacity—serving lavender farms from Missouri to New Hampshire. Bringing propagation fully on-site remains a key goal so winter work can happen where the work lives. It’s the kind of shift that doesn’t look dramatic on social media and yet changes everything for the people doing the work.

Ellen started gardening and it got out of hand.

The Butterfly Inflection

Fourteen years ago, Ellen noticed what the gardens were already doing. The precise mix of host and nectar plants—chosen first for herbs and beauty—quietly supported thirty-two native butterfly species. Beagle Ridge formalized that reality, added daily care, and invited visitors to learn what the plants were saying. The effect was two-fold. People who didn’t initially care about herbs arrived for the butterflies and left talking about the symbiosis between plant and pollinator. And when the lavender rows were harvested and the purple receded to “little green bushes,” butterflies kept wonder alive. Seasonality didn’t disappear; it softened. The farm’s living calendar developed more pages.

People who didn’t initially care about herbs arrived for the butterflies.

TODAY’S CONVERSATION

With a Genuine Garden Wizard — Curiously Impressed, Inspired, and Blessed

When I started digging into Ellen’s work I honestly felt a little overwhelmed — the list of projects, products, programs, and partnerships kept growing the more I read. I knew right away this would be a longer piece than I usually write, and even now I worry I haven’t done her full justice. Still, what stuck with me the most from our conversation wasn’t the scale of the operation but the way Ellen embodies it: grounded, easy to talk to, quietly generous, and brimming with practical wisdom. Her knowledge feels earned and unpretentious, the kind that arrives from doing hard, steady work over many seasons and then gladly showing others how to do the same.

Talking with her felt like meeting a living version of the kindly herb-teacher archetype — think Professor Pomona Sprout if she were real, less caricature, infinitely more interesting. Ellen is, in short, a wizard of her craft: curious, generous, and unfailingly kind. It was a genuine blessing to speak with her, and I’m already looking forward to more conversations and to following the next chapters of Beagle Ridge Farm—Lavender and Herbs

Teaching the Trade, Sharing the Map

Beagle Ridge didn’t plan to become a school, but once the pattern revealed itself, Ellen leaned in. For eight years, the Lavender Academy has offered three weekend-long intensives per year, a practical curriculum that covers how to grow lavender, how to start a farm, how to harvest and process, and how to turn crops into viable product lines. Local tourism officials—who have championed Beagle Ridge from the early days—recognized the draw, and when recovery funds appeared to bring visitors back, they offered to underwrite a venue. A sponsor covered Saturday night. The result: a conference that returns each April and has already welcomed attendees from as far as New Zealand and Jordan and from thirty-nine U.S. states.

Now, the work scales from program to institution. The Lavender Association of America will be unveiled in January, an effort designed to support smaller farms with shared standards, legal structure (with grower-attorneys lending pro bono expertise on 501(c)(3) and 501(c)(4) formation), training, and a network that keeps value in the communities where lavender is grown. In spirit it is exactly what Beagle Ridge has modeled on the ridge: not centralization, but connection.

Local tourism officials…have championed Beagle Ridge from the early days.

Collaboration over Competition

Ellen’s blueprint borrows a page from Virginia wine country’s playbook. Decades ago, the region encouraged clusters—five wineries within an hour of each other—betting that visitors wouldn’t stop at one. They were right. Proximity created gravity; everyone benefited. The same pattern is transforming the lavender landscape of Southwest Virginia. Today there are fourteen farms, with two more opening next year; many of those owners are Academy alumni. When Ellen says, “I want them to go to all of them,” it isn’t magnanimity for its own sake; it’s strategy. Similar models do not create sameness because people do things differently. Different gardens, different hands, different ways of welcoming. Diversity draws more visitors, and more visitors create a healthier local economy.

On closed days, Beagle Ridge teaches off-site—wine bars, wineries, breweries, pottery studios—meeting people where they gather. In North Carolina, three classes are already on the calendar with a long-time collaborator. Names ripple through the network: hybridizer Lloyd Traven of Peace Tree Farm, Shelly of My Garden Blooms, Debrena Gordon (Katherine’s mother, a soapmaker and grower), and Delaware-based alumna Laura Brittingham. The point isn’t celebrity; it’s a living commons that shares knowledge without hoarding it.

Proximity created gravity; everyone benefited.

Succession Without Surrender

Ellen is seventy this year, turning seventy-one in December; her husband is seventy-two. They are not retiring so much as moving the center of gravity. Katherine—the farm manager—has been with Beagle Ridge eight years and has been known to Ellen since childhood. She handles most of the product development now. The family placed assets in trust and built a house on the property; Katherine moved in last fall. The plan is explicit: preserve the work and the way of working. As Ellen’s husband put it, “we’ve done too much work here just to close it.” Selling might preserve operations, but not necessarily the character. The succession plan aims to keep both.

The farm’s practical theology is that reality gets a vote. Bears ended the on-farm beekeeping after three attempts—even with eleven-thousand-volt fencing—so Beagle Ridge buys honey. Weather sets the pace. The road in will always be the road in. But the operation hums through winter and bloom alike because its engine is broader than a single crop; it’s relationships, processes, and a thousand small habits that add up to continuity.

“In the off season, there is no off season,” Ellen says with a smile that is not quite a joke. Off-season is when you graft next year’s possibilities onto today’s routines: greenhouse planning, curriculum updates, conference speakers, recipes tweaked, labels redesigned, slow maintenance in the field, bookkeeping at the desk. The ridge breathes a different way when the gates are closed, but it never sleeps.

What the Name Means Now

As the twenty-fifth year approaches, Beagle Ridge will rebrand from Beagle Ridge Herb Farm and Environmental Educational Center to Beagle Ridge Farm–Lavender and Herbs. The shift is less about ambition than accuracy. Education continues, but the core of the work has clarified. The new name fits what the ridge has become: a place where a tourist might leave with a bar of summer pressed into soap, a local might leave with a plant ready for a new bed, and a student might leave with a business plan in a notebook and lavender in her fingernails.

Rebrands often signal a pivot to something shinier or bigger. Here, it’s a way of telling the truth in fewer words. The farm grew up; the name is catching up.

A Personal Note:

Why it Matters for a Parallel Economy

Argentabraid was born to surface stories like this — work that grows from a sense of place and grows, in turn, the places we live. Beagle Ridge offers a quietly radical template for an economy that doesn’t merely resist consolidation but outperforms it where it counts: in resilience, in knowledge held in common, in wealth that circulates locally and lands in real hands.

Conclusions: A Commons That Works

The numbers are the easy part—105 products, thirty-two butterfly species, 25,000 plants, forty-three countries of visitors, twenty-six wholesale partners. The harder part to count is the patience, the trust, the accumulated competence. You feel it in the way an elder shows a novice how to pinch a stem just so, in the way a group of strangers kneel in a row to pull weeds and then stand up laughing, in the way a tourism official finds venue money for a new conference because the ridge, improbably, draws people in.

It is collaboration over competition, yes, but it is also a wager about what people want. They do not only want products; they want provenance. They want to see where the thing they buy came from, to know who made it, to breathe a little valley air with the scent of the soap. They want to learn enough to try a version of it themselves. Beagle Ridge—remote by design—lets them do all of that and then, without fanfare, sends them back out into the world carrying a bar, a plant, a skill, and a story.

The farm’s future will include what the past has taught: a greenhouse that shortens the distance between decision and propagation; an association that gives small farms voice and structure; a conference that convenes peers who might otherwise feel alone; a manager who takes the helm with both reverence and curiosity. The butterflies will still need feeding. The batches will still need bottling. The road will still be the road. And there will still be, out there, a driver crossing the region who takes the exit because intention has become habit and habit has become tradition.

“We’re a place people seek out, not stumble upon,” Ellen says. It’s a line that doubles as strategy for how rural places can thrive. Make something real enough that people will rearrange a trip to touch it, again and again. Teach what you know. Share the map. Put enough destinations within an hour that nobody visits just one. Leave room for other people’s hands to matter.

Help us keep sharing real stories

Do you know someone growing something beautiful, building something bold, or living in quiet alignment with their values? We’re always looking for voices to feature — makers, growers, dreamers, and doers who are part of the parallel economy and the heart of what we stand for.

Reach out to Alary Woods at:

bc1q06zmqydvua968pkplh8y6ymnuxkqh9w2k9z6eg